The Roots of Environmental Justice

Professor Ashwin Ravikumar is an assistant professor of Environmental Studies. His research interests involve deforestation in the Amazon. This semester, he is teaching a class entitled “Environmental Justice” about the intersections between environmentalism and other forms of social justice. I sat down with him (over Zoom) to talk about environmental justice; he defined it as: “Environmental justice is a movement that explicitly recognizes that environmental issues are inextricably connected to racism, capitalism, patriarchy, and other forms of oppression.” He then talked me through the genesis of the movement.

The ideas of intersectionality in social justice are not new; environmental justice has roots going back to the late 70’s. Ravikumar describes some of the first rumblings of the environmental justice movement. These were happening concurrently all over the country, but the key example is in Warren County, North Carolina. “There was a movement around this polychlorinated biphenyl or PCB, which is a toxic compound, dumping site… near this predominantly black community. [This movement] led to organized protests to resist the facility, along with education and organizing efforts to explicitly recognize that the impacts of environmental contamination are not experienced uniformly and that they disproportionately impact black communities, communities of color, and low-income communities.

“That was really where the environmental justice movement started. And since then it has sought to push for policies, organize communities, and do other things to deal with what we call environmental racism; essentially, that disproportionate impact of environmental contamination on communities of color.”

Professor Ravikumar explained in more detail how social and environmental issues intersect. “I think it’s important to recognize that environmental problems are created by economic systems and social relations. By the 1960s, we were seeing massively more degradation of natural ecosystems alongside the relegation of communities of color and especially urban areas around the same time. A mainstream environmental movement coalesced out of a recognition that pollution was causing public health issues and damaging ecosystems at the same time.” The movement led to several legislative victories, including the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Clean Water Act, and the Clean Air Act.

However, not all Americans experienced these advances. “Part of the way that [the civil rights and environmental movements] are really connected on a structural level is that as the US became wealthier… black communities were denied access to a share of that wealth through racist housing policies known as redlining. Basically, they would draw maps of cities that made it impossible for people of color, especially black people, to buy houses in many parts of the city. This process created spaces where people were politically disempowered, were economically worse off, they couldn’t accumulate wealth through the increase in housing values, like white folks were doing. Those same communities were over-policed and politically disenfranchised which made it really easy for polluting facilities to dump toxic waste there, and we’re seeing the legacy of that right now. Essentially, the waste products of industry that produced a lot of wealth for a lot of people needed somewhere to go, and the place where that went is to communities that were systematically disenfranchised through policy after the second world. There’s a straight line between those two things that I think really connects social issues and environmental justice issues.”

In 2020, we are still seeing the effects of such policies, as Professor Ravikumar pointed out.

“Covid-19, which disproportionately affects black people, is intimately connected to this history of unfettered industry and housing discrimination. Respiratory problems that black communities and communities of color in general as well as low income communities face as a result of this kind of history, and having polluting facilities disproportionately cited in their communities, are exactly what makes Covid-19 so much worse, and that’s why we’re seeing such an outsized impact of Covid-19 on black communities in particular compared to white communities.”

Professor Ravikumar’s Background

I asked Professor Ravikumar how he got into environmental studies and came to focus specifically on environmental justice and deforestation. Though he was never directly impacted by environmental injustice growing up, he “came to work on these issues out of deep concerns about inequality, which maybe I was more aware of than some other kids that are from well-off suburbs in the US. I would visit India as a kid and see stark inequality and I guess my political instincts as a child were that war is horrifying, and extreme inequality is nauseating. I’ve probably yet to really improve on those instincts and they continue to guide a lot of what I do, but as I learned about climate change in college, I started to see these issues as really connected.”

In college, he studied ecology and environmental biology with a focus on social issues. He graduated in 2008, just as the economy crashed, so he then went to grad school; there weren’t many other options. “My advisor happened to be working on issues around deforestation in Latin America, and I ended up finding it really interesting. I had a few really amazing job opportunities before coming to Amherst that put me pretty close to the center of vital decision-making about forest policy, land use, and Indigenous rights. I found that I was able to be helpful as a conduit for funds to indigenous groups primarily in Peru, which is where I’ve done a lot of my work, and as an organizer of data and social scientific information that could be used to support indigenous groups and trying to get rights to lands that were traditionally theirs and that they had protected recently.”

Professor Ravikumar went on to explain why this work is so vital in the fight against climate change. “Part of the reason tropical forests are so important is because they are massive carbon sinks. When we lose tropical forests, all of the carbon that’s locked up in the soils gets released into the atmosphere and we lose the capacity for those forests to reabsorb that carbon, which is super important for mitigating climate change. I started to care about the Amazon because I saw that it was so important for the global climate, and it was also a place where there was just so many intersections of other issues that are important, especially around indigenous writings, which is a major part of what I think of as environmental justice.”

Before coming to Amherst, Professor Ravikumar worked at the Field Museum in Chicago. There, he was involved with advocating for arrangements between governments and indigenous communities which allow these communities to continue to live on and protect their ancestral lands. This project involved creating programs for more government support and making sure the protected lands were not easily accessible to tourists. “It’s one of the places that you know where I learned just a tremendous amount and I still have a great relationship with them.”

The Future

After learning about Professor Ravikumar’s background and research interests, I asked my burning question: As someone involved in environmental justice and political ecology, is there any hope for the future?

His answer, in short, was that he has good news and bad news. He started off with the bad news: “Unfortunately, it is hard for me to imagine a 21st century where we limit warming to less than three degrees Celsius, and it’s hard for me to imagine a 21st century that avoids a soft genocide of millions of people who will perish in disasters, destructions of the coastlines, and brutal conflicts. But there are always different possible worlds; the difference between a world that is three degrees warmer and a world that is five degrees warmer is almost incomprehensibly massive.” The future also depends on the path we take, whether that is militarizing borders to keep out climate refugees, or a public investment in paying America’s outsized climate debt. Regardless of the path, Professor Ravikumar thinks that terrible things are bound to happen.

However, there is some hope if we frame this in a different way. “If we take a longer view of history, which I’ve been challenging myself to do lately despite it being really hard, I keep coming back to realizing that what we do right now and right here actually does matter a tremendous amount. We have to move away from fossil fuels. We have to address environmental injustice by editing the policing and incarceration of black communities and communities of color while investing in those communities according to a logic of reparations. We have to allow those very groups that have been most marginalized to participate and lead in envisioning a better world that works and thrives in harmony with nature and does not depend on the economic systems that we know are so damaging.”

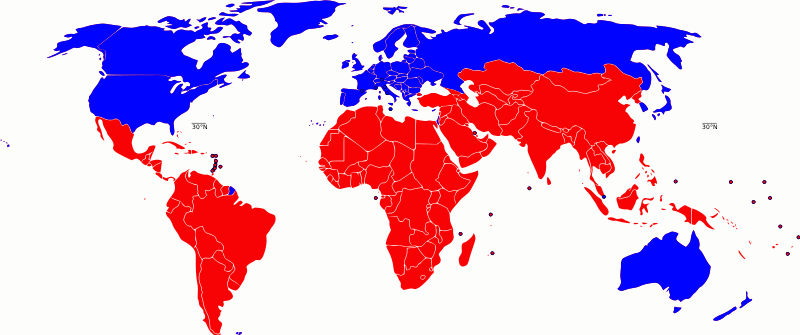

Professor Ravikumar discussed the global side of environmental justice as well, including massive debt forgiveness for the global South because paying that debt would be an indefensible blow to those countries and their economies. He noted that “this would allow people in the global South to regain control over their economic decisions. They could more easily arrange their economies around meeting human needs and protecting ecosystems instead of producing cheap consumer goods that degrade the environment for global markets.” This would also stop the flow of cheap consumer goods to the global North which do not affect our lives in a meaningful way. “Global South” and “global North” are relatively recent economic, not geographical, descriptors to replace value-based qualifying terms such as “first world,” “third world,” or “developing countries.” The Global South describes newly industrialized countries typically with a history of being colonized by Global North countries.

Photo: Wikipedia. The global North countries are shown in blue, and global South countries are shown in red.

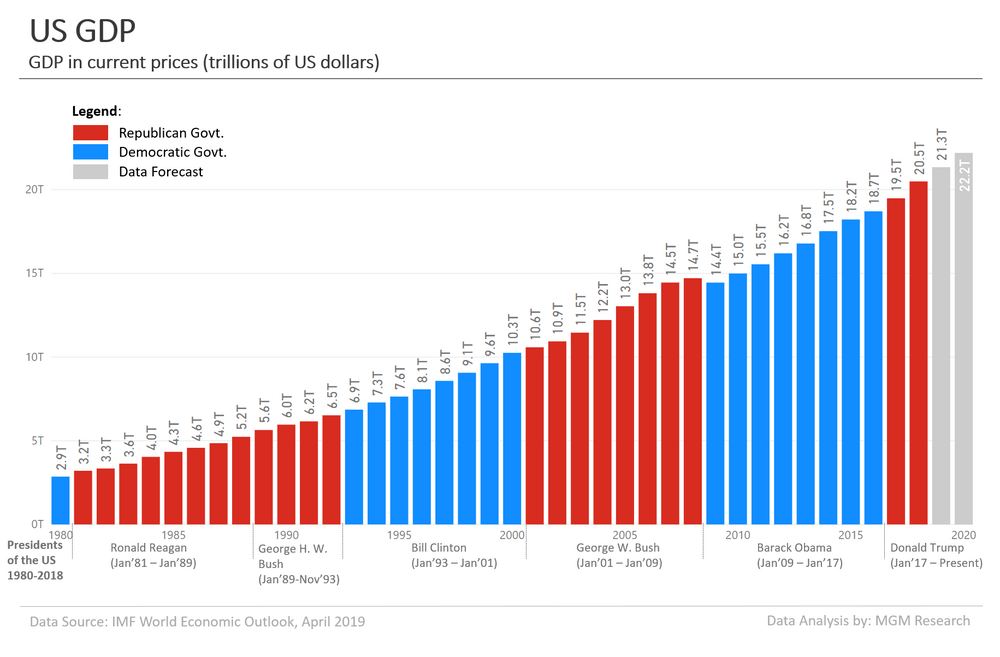

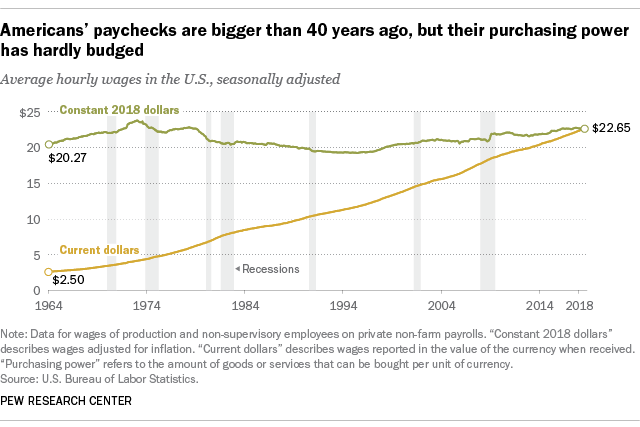

Professor Ravikumar believes our lives will be different; we have to drive less, drastically change food systems, and organize politically against great resistance to create this change. For the global North, GDP (gross domestic product) has increased for the last 40 years, but other measures that actually quantify human well-being such as poverty and wages are stagnant. All the economic growth has not translated to a higher quality of life, so “clearly there’s a lot of room to reallocate our public resources towards building a world that does not accelerate the most dreadful version of a climate future and instead builds a much better world.”

Image: ,,https://mgmresearch.com/us-gdp-data-and-charts-1980-2020/

What We Can Do

After hearing this intuitive but daunting list of what humans need to do to get our world back on track, I asked Professor Ravikumar what we could do, as individuals, to promote environmental justice and sustainability. Calling your senator and showing up at a protest are good, but demonstrate the next level of commitment and join an organization that is actively working to better your community. He gave two main tasks:

First: “Organize. Find ways to impose costs on decision-makers who won’t stand up to polluting companies or polluting industries, who are tepid about taking bold steps to reinvest resources in black and brown communities to make us less reliant on fossil fuels.”

The second: ”Link up with a local group that’s doing work that resonates with you. Go to a meeting, volunteer to take notes, and figure out how you can plug in. I really think that that’s the best way to participate in the process of imagining and actually bringing about a better world.”

Think about the resources you have and how you might be able to use them to support marginalized people and the work they are doing. Donate your money or your time to organizations affiliated with Black Lives Matter, to one of many local environmental justice groups, to a national environmental movement like the Sunrise Movement, or many other groups promoting social justice. Essentially, be a kind and compassionate human.