In 2007, a performance artist named Stelarc permanently integrated a synthetic ear into one of his arms in hopes of “amplifying” his body. As unorthodox and unrealistic as this sounds, it offers an iconic example of BioArt: an art practice where artists and researchers work with cells, tissues, organisms, bacteria, and even organs such as ears to create artwork.

Stelarc poses under the light that illuminates the “third ear” he implanted underneath his arm. Image credit: ,,stelarc.org

Bridging together the two often independent fields of art and science, “BioArt” as an artistic practice was first adopted by a Brazilian-American artist and professor named Eduardo Kac in 1997. In his performance Time Capsule, Kac implanted a microchip into his left ankle and registered himself as both the animal and the owner in the pet database. Incorporating biometrics into his performance art, Kac aimed to force his audience “to consider the co-presence of lived memories and artificial memories within us” and the “ethical implications of such procedures in the digital culture” while demonstrating how science can be used as an art medium.

Eduardo Kac showcases the moment of the microchip insertion to a group of photographers. Image credit: ,,ekac.org

However, BioArt is not solely about large-scale installations by artists like Kac and Stelarc; in fact, most BioArt is produced from everyday experiments that use biotechnology such as MRI, gel electrophoresis, and crystallography. If you have ever found a picture in your biology textbook oddly aesthetic, you just found yourself a BioArt.

.

.

Left – Image of an embryonic Little Skate sitting atop its yolk sac. Image credit: Katherine O’Shaughnessy and Martin J. Cohn at University of Florida and Howard Hughes Medical Institute

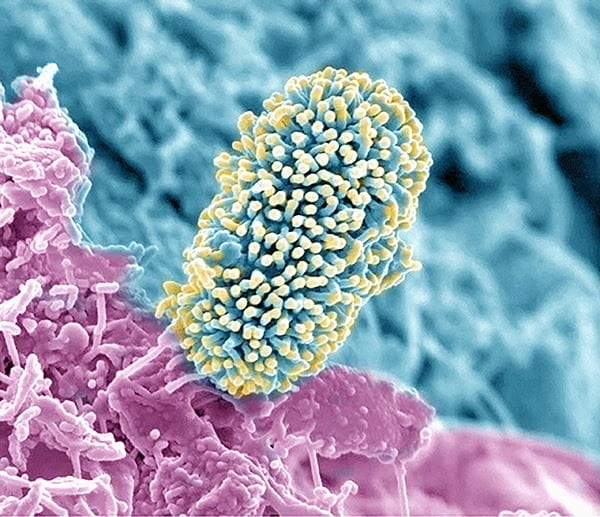

Right – Electron scanning microscopy image of a soil bacterium on the root surface of an Arabidopsis plant. Image credit: Alice Dohnalkova from the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory

Although the picture you came across was lucky enough to be published, thousands of images and videos go unpublished and unseen outside of the laboratory. To showcase these works and shed light on the beauty of scientific research, the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), among other organizations, began their annual ,,BioArt Scientific Image & Video Competition in 2012.

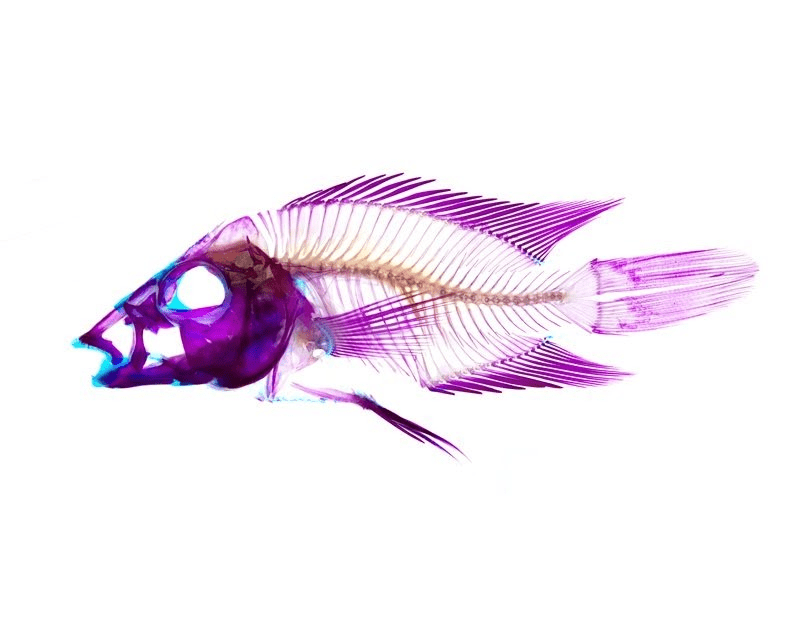

This year’s FASEB BioArt Competition featured works from a geometric print of filamentous viruses to a kaleidoscopic image of a mouse skin, illustrating the diversity and breadth of scientific research happening all across the country. Among these works was a chilling image of a South American cichild created by M. Chaise Gilbert, a PhD candidate from a craniofacial lab at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Cleared and stained image of Caquetaia spectabilis, a South American cichild highlighting the extreme jaw protrusion that this species is known to have. Image credit: M. Chaise Gilbert of University of Massachusetts, Amherst

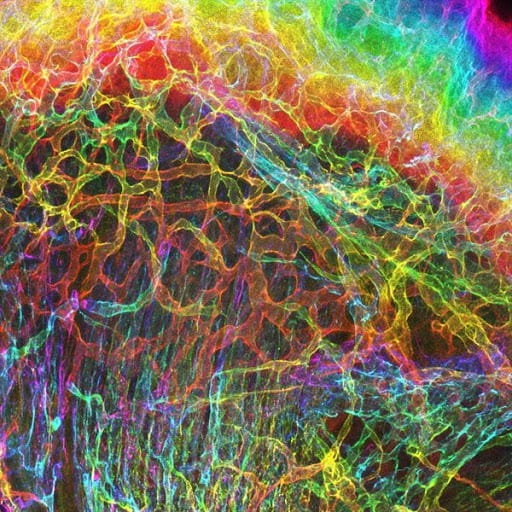

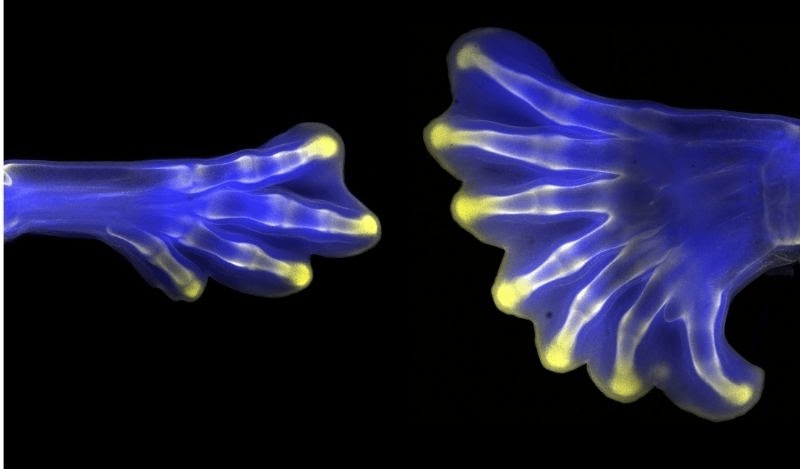

What’s unique about this sphere of BioArt is that they are practical. In regards to this frightful yet enticing image, Gilbert commented, “Images like this are being used to better understand how extreme morphologies can introduce anatomical and functional tradeoffs.” Similarly, the image above of the developing skin/muscle interface helps researchers understand how limbs develop and thereby help engineers study different ways to treat musculoskeletal injuries.

Below are some of the other eye-catching works recognized by FASEB this year.

.

.

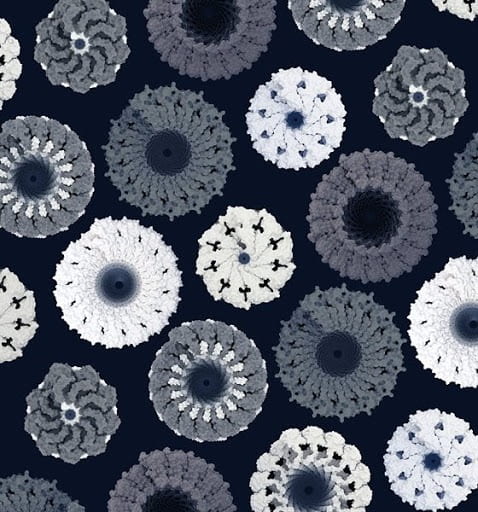

Left: Image of an ensemble filamentous viruses. Image credit: Edward H. Egelman.

Right: A 3D color projection of developing skin/muscle interface of a mouse. Image credit: Sarah Lipp

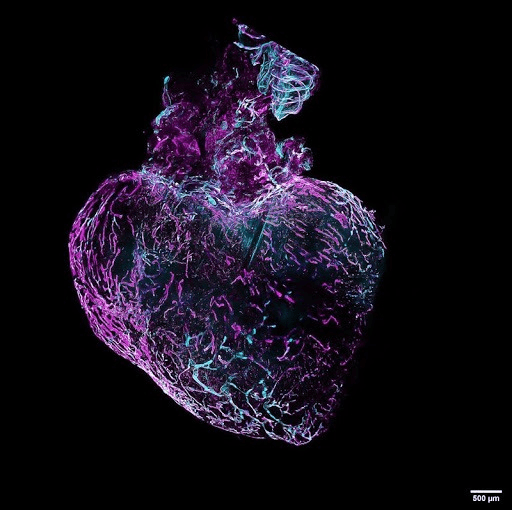

A 3D evaluation of cardiac lymphatic network remodeling of a mouse. Image credit: Coraline Héron

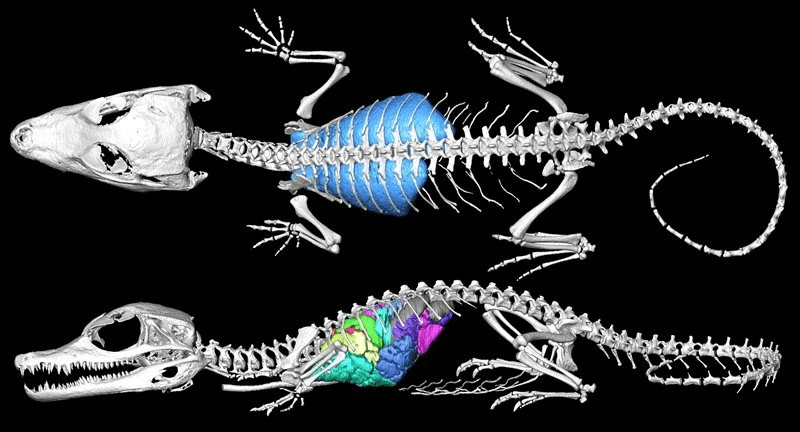

An image of a 3D segmented model of the lung surface, bronchial tree, and skeleton of a Cuvier’s dwarf caiman. Image credit: Emma Schachner

Image of two hindlimbs from chick embryos. Image credit: Christian Bonatto

As these winning works and the aforementioned performances illuminate, the realm of BioArt is expansive yet unique, alluring yet practical. If you are a researcher here at Amherst College, you may even consider entering the FASEB’s BioArt Competition to share the beauty of your scientific work with the world.